Follow

Wellness & Co.

Hi, I'm Dr. K, Wellness & Co. is a growing therapy/coaching practice and educational hub for prospective clients based in Maryland and virtual clients all over the world!

Hi, I'm Dr. K

free guide

e -books

e -course

We Need To Talk About ADHD In Girls

October 15, 2024

Part II: The Empowerment of an ADHD Diagnosis

By: Rebecca Horch, BACYC, CPC

Welcome to part 2 of our 3 part series about ADHD. These posts are meant to inform and educate, and you may find that you connect with them, either on a personal level or because you have someone in your life who you are thinking of as you read. As I share a part of my story with each post, how we can support our own children and some tips for understanding ADHD, I encourage you to check in with yourself and notice if anything in particular resonates with you. And if it does, please feel free to reach out for support.

Trigger Warning: Self-harm

My Story – The Invisible Struggle

Because I got good grades I was never flagged as having any real behavioral or academic challenges even though on the inside I was struggling. It felt like everyone around me had so much more control over the things they said, the energy they had, and the ability to focus. My brain seemed to be either constantly fuzzy, causing me to never quite meet expectations. Or, the exact opposite. Full throttle and unable to turn off.

Generally, teachers liked me. As I grew older and learned how to mask my impulses, I didn’t disturb the class in traditional ways. I wasn’t overly hyperactive, and could sit still if I needed to. Usually, I would get called out for chatting with friends, or not paying attention. My biggest challenge in school, other than being incredibly unorganized, was that I’d get bored so easily. I had to find ways to keep my interest in order to function as a student.

If I didn’t find something pleasurable to do in the unpleasurable moments it was as if my whole body would fire up. The boredom hurt physically. My skin would crawl with what felt like thousands of spiders and I’d just want to rip it off.

If I didn’t doodle while listening to the teachers, my mind would wander. If I didn’t get up and “go to the bathroom” every 20 minutes I’d start tapping my legs, or pencil on the desk and get in trouble for disturbing the class. If I didn’t write poems and stories in the margins of my notebook, I’d be unable to actually hear what the teacher was saying. Sometimes the students around me would say “Rebecca, what are you doing?” and I’d realized that I had been talking or humming quietly under my breath, creating wild stories in my mind to get through the class. To them, I must have looked a little strange. To me, it was my way of functioning in a system that was not built for a brain like mine.

At home, my silent struggles mixed with the hormonal ups and downs of adolescence left me exhausted, overwhelmed, and emotionally unwell. I often got reprimanded by my parents for things like never having a clean room, or not doing my chores. What seemed like normal adolescent disrespect to them, was actually an inability to complete tasks around me. I began self harming to deal with the shame I constantly felt for not quite fitting into the social norms all around me. However, even my self harm wasn’t traditional. The marks I would carve into my skin were often creative designs, pictures, or lyrics to favorite songs. To me it didn’t even cross my mind that this could be a problem. I was simply giving myself tattoos.

When it came to friendships, I was desperate to fit in. Now and then I would find myself in what I now realize were incredibly dangerous situations, often resulting in someone being hurt, and a couple of times being cornered into something I was not ready to do. And each time, I couldn’t quite seem to “learn my lesson.” Ultimately, it all boiled down to the shame I carried that I had to do and be a certain kind of person for people to accept me. I’m thankful now for what I hated then- strict parents who kept track of my comings and goings. Without that, I am certain I would have encountered many more of these situations and I’m so thankful now I didn’t.

Along came adulthood and my first years at university. The lack of structure that I had in high school left me floundering. I could write a well researched paper, but would forget to hand it in on time. I could build a beautiful presentation, and feel confidently prepared, but would accidentally delete it the day before it was due. I would often show up to the wrong class, at the wrong time, in the wrong building. I’d forget my notebooks, forget to bring food even though I’d have classes all day, and ultimately, I felt completely lost, incapable and inadequate. I scraped my way through the first couple of years of university, and eventually found a groove that I was able to settle in to help me succeed, but again, I could not quite understand why for most students it just seemed so much easier.

It was this challenge through university that impacted my future career. I had always dreamed of school. I loved to learn, and still do, but because I was so afraid to fail and struggle like I did in my first couple of years, I chose an undergraduate major that I felt was “easier” than what I really wanted to do. Because I chose this degree, my options were limited and if I had wanted to complete a Masters at the time it would not have been possible without multiple bridging classes. This extra coursework seemed so daunting and so I put it off. Instead of going back to traditional school I began certifying in areas that were intriguing and kept my interest – this is what I now know is the number one most important thing to know about the adhd brain: If the interest isn’t there, it can truly feel impossible to complete.

However, these certifications, although powerfully impactful and specialized, still didn’t put me in a place where I felt “good enough” amongst my peers. These seemingly minute decisions in my career created deeper and deeper shame spirals that followed me through young adulthood. As I watched my peers succeed, it felt like I was working so hard to simply scrape across the finish line, exhausted and beat up. Although I was specializing beyond what my peers could achieve in traditional settings, I still didn’t feel like I measured up to them.

Shame carries with you when you have adhd. The little girl who was told a story that she would never live up to her potential simply did what she was told. Turns out our potential comes in all shapes and forms, and I was only seeing one side of that. It wasn’t until I befriended this shame and brought her healing that I learned to lean into my strengths and recognized my gifts.

If you recognize yourself or your child in any part of this story so far, you are not alone! There is space for self compassion and inner healing. There are very specific ways that we can work with shame associated with having a neurodivergent brain. Please reach out if this connects with you and you want to learn more.

Your Daughter – The Importance of Coaching/Therapy

You might be wondering at this point how you can take these clues you may be seeing, and the concerns you have for your own child and DO something about them? I cannot stress enough the importance of finding both personal support for yourself, and guidance on how to help your child. I have worked with dozens of parents who find themselves really lost in knowing how to show up for their kids, and in the meantime they end up struggling with their own mental health. Truly the best approach is a whole family, wraparound model where you are all getting the support you need, and that will be unique to each individual family and each individual member of the family.

In my story, it was later in my life that I started seeing a counselor sporadically. I began to notice in my daughter signs of what I thought might be a neurodivergence. At this point, I had been working with youth and families for a long time, and so I thought I had a good idea of what it must be, but it never even occurred to me that this might be me as well. One day I consulted with my counselor and he gave me some recommendations on how to get her assessed, and he also gave me my first clue that maybe this is something I’d like to look into myself.

He said “most children with ADHD will have a parent with ADHD too”.

After multiple forms filled out by teachers, blood work done, and even a brain scan, she was diagnosed with ADHD in the first grade. We decided not to medicate at the time, but the diagnosis in and of itself was like a breath of fresh air. Finally, an answer. Even for her, it felt like a magical sword. She had a name for why she would so often get emotionally dysregulated or why she would lose track of time so easily. There was a reason why her low frustration tolerance was so acute. And now we had a diagnosis we could take to her teachers so they would know how to help her thrive. It was an incredibly empowering experience.

Once we received my daughter’s diagnosis I went into overdrive in learning how I could support her. It became like an obsession, and I started reading all I could and taking as many mini courses as I could about ADHD. The added bonus of what I now know was “adhd hyperfocus” (a symptom of ADHD) is that I became a bit of an expert on the topic, and it served me really well in my career. I began working with parents to help them to learn how to support their own children, and understand their neurodivergent brains.

After her diagnosis, not only was I finally able to show up for my daughter in a way that connected deeply to her needs, but I could also teach other parents about how to do the same for their children.

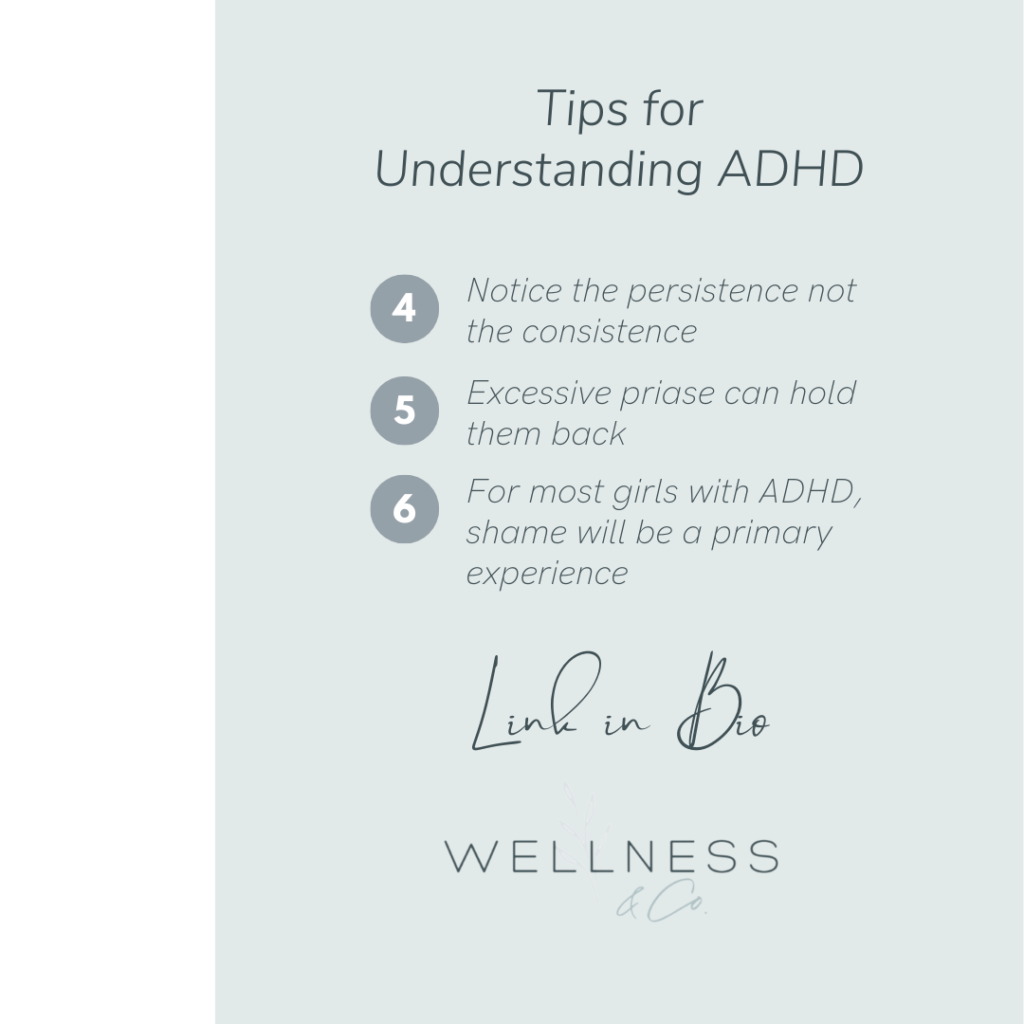

Tips for Understanding ADHD:

Remember: If you are someone who knows a young girl or a woman in your life who has ADHD or you suspect has ADHD and you want to know some practical ways you can support them right now here is some basic education & strategies:

Tip Four – Notice the Persistence not the Consistence

People with ADHD may struggle with consistency, but they will almost always have an admirable tenacious persistence. They will get up and try again and again. Notice this. Name it.

Tip Five – Excessive praise can hold them back

Surprising right? But remember, supposed “failure” is inevitable to people with ADHD. When we overly praise a behavior or a skill, it can feel very scary to a person that knows they may not be able to meet that expectation in the same way again.

Tip Six – For most girls with ADHD, shame will be a primary experience

Many girls spend years trying to “mask” symptoms to fit in, creating a hidden part of themselves that feels as though it will never be welcomed. You can attempt to mitigate this developing shame by providing a safe haven for the person to let their brain do their thing. Working with what they got, without judgment and with curiosity is truly the most effective way to work with the shame that can show up. Create environments for them where they don’t have to “work with the system,” but that “the system is working for them.”

Rebecca strives to support others in building resilience, self-compassion, connected relationships and self-awareness. She loves to work with people who are ready for the hard work of inner growth and is passionate about helping others tap into their intuitive gifts and use them in this world.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

CONTACT

Start Here

BLOG

OUR TEAM

SHOP

ABOUT

©2025 Wellness & Co. | All Rights Reserved | Design by EverMint Design Studio

BACK TO TOP

connect with us on instagram